Because you don't. Owning, as I do, a mind as reliable and watertight as the average game of Ker-Plunk!, I have learned to become something of a note-taker. I jot stuff down, anything, everything, as it occurs to me – yes, on trains, or planes, or sofas, or seesaws, or the queue at Tesco – so I don't lose it. I use notebooks, old envelopes, Post-its, the backs of shopping lists, the foreheads of passing children, whatever's to hand. Then, when I actually need an idea, professionally speaking, I rifle through this scrap-head resource and eventually come up with something that makes me go 'Oh, yeah, that'd work.' Except, of course, for the occasions when I find something that makes me go, 'What is that? A "B"? What's that word? Did I write this?'

So I'm delighted to be able to say that in the case of Eisenhorn (which is the umbrella title we've given to the cycle of novels and linked short stories collected in this spiffy volume), I know exactly where the idea came from. Not me, that's where.

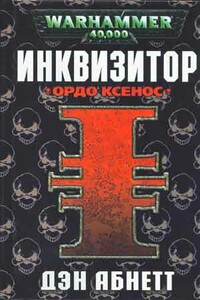

There is a rather gorgeous painting that many of you, I'm sure, will be familiar with. It's called Inquisitor Tannenberg, it's by John Blanche, and it has been reproduced in various places, including the Incjuis Extermi-natus. Know the one? Guy with a scalp full of cables, a black fur coat, a

double-headed eagle familiar on his shoulder, a gold-chased bolt pistol in his hand? Yes, it's is good, isn't it?

I'd been working for the Black Library for a few years, producing a variety of things, most notably the Gaunt's Ghosts novels. So the grim nightmare of the far future, where there is only war and the galaxy's alight and everyone's got a headache, was pretty much my thing. The editors kept me fed with all the latest fluff and hot new supplements, just to keep me in the loop. And one day, they sent me this pile of photocopies: sketches, paste-ups, notes. There was going to be, they told me, a new game called Inquisitor, and they were so jazzed by the concepts and ideas coming out of the game's development, they decided to send me all the stuff, hush-hush, in the hope that it might inspire me, Gaunt-wise.

As soon as I opened the package and started leafing through, I could see what they meant. This was a rich seam indeed, full of wonderful baroque material. Among the pages, along with a number of other very fine pictures, was a copy of John Blanche's painting. And that was it. I picked up the phone, called Black Library and said, 'Can I please write about this?' Even though, truth be told, at that stage I didn't know exactly what 'this' was.

They said yes (I think they sensed the enthusiasm in my voice). The idea was that if I could write the novel quickly enough, it could come out AT THE SAME TIME as the game launch, and everyone would look big and clever, like it had been planned that way all along.

I visited the Studio, and got great help and advice from the game developers, particularly Gav Thorpe. Then I got to work.

I think what inspired me about John's painting was the aristocratic clothing: the rich black velvet of the sleeves, the engraved gold of the elegant weapon. This wasn't about the battlefield, the front-line of mud and gas and behemoth engines. This was a glimpse behind the lines at the internal complexity of the Imperium. It offered a chance to explore what might be called the 'domestic' side of the Warhammer 40,000 universe: the daily, non-military, life – at work, at worship, at rest, at court, at slum-level. A chance to visit worlds that were not levelled by war, and see how the billions of Imperial citizens lived.

And also to find out what evils stalked them, even in the shadows of their own hive cities.

The novel turned into a trilogy that charts the career of a man. Other stories, two of which are collected here, lace into that trilogy and, for those who are interested, the exploits of several of these characters continue in the Ravenor novels that are my current concern.

John Blanche's images have always had such a profound influence on the growth of the Warhammer 40,000 universe's unique flavour, I'm proud to acknowledge that painting as the inspirational source of