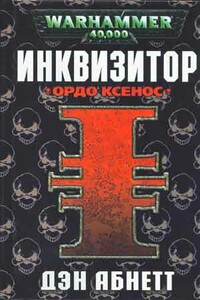

I had made sure I was sitting in an armchair when Bequin showed them in so I could rise in a measured, respectful way. I wanted them to be in no doubt who was really in charge here.

'Minister Hansaard/ I said, shaking his hand. 'I am Inquisitor Gregor Eisenhorn of the Ordo Xenos. These are my associates Alizebeth Bequin, Arbites Chastener Godwyn Fischig and savant Uber Aemos. How may I help you?'

'I have no wish to waste your time, inquisitor/ he said, apparently nervous in my presence. That was good, just as I had intended it. 'A case has been brought to my attention that I believe is beyond the immediate purview of the city arbites. Frankly, it smacks of warp-corruption, and cries out for the attention of the Inquisition/

He was direct. That impressed me. A ranking official of the Imperium, anxious to be seen to be doing the right thing. Nevertheless, I still expected his business might be a mere nothing, like the affair of the trade federation, a local crime requiring only my nod of approval that it was fine for him to continue and close. Men like Hansaard are often over-careful, in my experience.

There have been four deaths in the city during the last month that we believe to be linked. I would appreciate your advice on them. They are connected by merit of the ritual mutilation involved.'

'Show me/ I said.

'Captain?' he responded.

Arbites Captain Hurlie Wrex was the handsome woman with the short black hair. She stepped forward, nodded respectfully, and gave me a data-slate with the gold crest of the Adeptus Arbites on it.

'I have prepared a digested summary of the facts/ she said.

I began to speed-read the slate, already preparing the gentle knock-back I was expecting to give to his case. Then I stopped, slowed, read back.

I felt a curious mix of elation and frustration. Even from this cursorial glance, there was no doubt this case required the immediate attention of the Imperial Inquisition. I could feel my instincts stiffen and my appetites whetten, for the first time in months. In bothering me with this, Minister Hansaard was not being over careful at all. At the same time, my heart sank with the realisation that my departure from this miserable city would be delayed.

All four victims had been blinded and had their noses, tongues and hands removed. At the very least.

The evangelist, Mombril, had been the only one found alive. He had died from his injuries eight minutes after arriving at Urbitane Mid-rise Sector Infirmary. It seemed to me likely that he had escaped his ritual tormentors somehow before they could finish their work.

The other three were a different story.

Poul Grevan, a machinesmith; Luthar Hewall, a rug-maker; Idilane Fas-pie, a mid-wife.

Hewall had been found a week before by city sanitation servitors during routine maintenance to a soil stack in the mid-rise district. Someone had attempted to burn his remains and then flush them into the city's ancient waste system, but the human body is remarkably durable. The post could not prove his missing body parts had not simply succumbed to decay and been flushed away, but the damage to the ends of the forearm bones seemed to speak convincingly of a saw or chain-blade.

When Idilane Fasple's body was recovered from a crawlspace under the roof of a mid-rise tenement hab, it threw more light on the extent of Hewall's injuries. Not only had Fasple been mutilated in the manner of the evangelist Mombril, but her brain, brainstem and heart had been excised. The injuries were hideous. One of the roof workers who discovered her had subsequently

committed suicide. Her bloodless, almost dessicated body, dried out –smoked, if you will – by the tenement's heating vents, had been wrapped in a dark green cloth similar to the material of an Imperial Guard-issue bedroll and stapled to the underside of the rafters with an industrial nail gun.

Cross-reference between her and Hewall convinced the arbites that the rug-maker had very probably suffered the removal of his brain stem and heart too. Until that point, they had ascribed the identifiable lack of those soft organs to the almost toxic levels of organic decay in the liquiescent filth of the soil stack.